So you want to write an "app"

After writing that (no-longer-)recent post on web development, I wanted to get a personal "feel" for what the "new developer experience" is actually like across all of the current platforms if you don't resort to web tech such as Electron.

I've been a computer toucher for decades, but I've never been an "app developer" and have always interacted with computing in an idiosyncratic way. Although I did build GUI programs using WinForms, I haven't been actively keeping up. This is therefore a gap in my skillset! So, let's try to close it!

This project began with a live-toot stream, and this post is a long-form summary and retrospective. If you want to peruse the code, you can find it here.

The "app"

For this experiment, I chose to write a program to generate random numbers in a user-specified range. This simulates rolling different types of dice with different numbers of sides, as would be used for DnD or other TTRPGs, and would be part of the long tradition of using computers to play games.

The idea behind choosing something "simple" like this was to focus my attention on the "tooling setup" and "basic UI building" functionality of each platform rather than the application logic.

In order to increase the difficulty and place some more attention on "platform integration" functionality, I eventually added the following additional requirements to the GUI applications (i.e. not the command-line ones):

- persistent settings (the number of sides on the dice is saved and reloaded)

- localization support into at least one non-English language

For each platform, I tried to use the tools, technologies, and documentation that were most prominently promoted and/or that I had the easiest time finding. Unfortunately, gone are the days where programmers would invest a lot of time to get to truly know a platform inside and out, but I tried to do my best to simulate a harried (but competent) programmer.

The platforms

I ported this program to the following platforms, in order:

- Standard C

- C/POSIX, command-line

- Linux with GTK and GNOME

- Linux with Qt and KDE

- Windows with WinUI 3

- macOS/iOS with SwiftUI

- Android with Jetpack Compose

Sarcastic one-liner awards

Although I learned a lot, the experience wasn't great. As such, I've chosen to award each platform its own unique sarcastic summary, which I will subsequently expand on:

- Standard C — Most resistant to obsolescence

- C/POSIX — Most useless standard

- GTK/GNOME — Most squandered potential

- Qt/KDE — Most screwed over by the platform

- WinUI 3 — Most uninspired

- SwiftUI — Most fun to waste time with

- Jetpack Compose — Most blatantly "mask off"

Standard C

To set the stage, I started this experiment by implementing the core functionality using only standard C. This is the programming language I myself started with over 20 years ago, so I assumed (hah!) that there wouldn't be anything for me to learn from this.

This initial program is short enough to be included right here in this post:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <time.h>

int main() {

srand(time(0));

while (1) {

unsigned int dice_max;

while (1) {

printf("Dice max? ");

int ret = scanf("%u", &dice_max);

if (ret == 1) break;

}

if (!dice_max) {

printf("Invalid!\n");

continue;

}

unsigned int rand_div = (RAND_MAX + 1u) / dice_max;

unsigned int rand_cap = rand_div * dice_max;

unsigned int rand_roll;

do {

rand_roll = rand();

} while (rand_roll >= rand_cap);

printf("Rolled: %u\n", rand_roll / rand_div + 1);

}

}

A lot of discourse about C nowadays tends to focus on its many (legitimate) problems with memory (un)safety, undefined behavior, and ABI hell, but none of that matters for an application like this. Despite all of its flaws, C is perfectly capable of representing programs like the one above which use structured control flow and perform simple text-based interaction with a user.

If anything, the fact that computing did manage to get to the point where I can write the above program once and then run it on any computer which implements the appropriate international standard... is an extraordinary achievement! If the above program were to be downgraded to only depend on C89 or K&R features (an exercise for the reader), it would run on computers stretching back across decades, and it will likely continue to run on computers for many years to come.

However, despite its great success at being a standardized language capable of expressing structured control flow while balancing the interests of innumerable interested parties, computing needs more than that, starting with "how does a user actually go about acquiring or otherwise running this program on a given computer?"

C/POSIX

Many developers including myself use "Unix-style" tooling regularly, so a reasonable thing to try and do might be to make this dice program work "like a Unix-style" tool. But what does that actually mean? How do you do that?

I'm too young to have lived through the era of the "Unix wars" and needlessly-incompatible differences between vendors, and so I'm lacking a lot of the historical context. However, attempts were at some point made to standardize Unix behavior into an IEEE standard called POSIX. This seems like a direction to start looking!

Except... how does a programmer starting out today even learn about POSIX? I happened to already know about POSIX because I've heard people talk about it over the years. I don't know that a novice programmer would necessarily come across it or believe it to be relevant, especially given the amount of time which has passed since the Unix wars and the amount of flaws the standard has (as we shall soon see).

One success of POSIX is that it specifies c99 as a standard executable name for a C compiler, and it specifies a portable subset of makefiles for building software from source. The subset which is standardized is enough to compile a simple application like ours:

.POSIX:

CFLAGS = -O1

dice: dice.c

clean:

rm -rf dice

(For those unaware, make has various built-in rules which know how to compile C programs! You don't have to write out explicit rules!)

Given a source code distribution with a single .c file and a makefile, someone familiar with "it's a Unix system!" should ideally be able to figure out to type make and ./dice to compile and run this application.

Is there a way to make this program "fit in" even better? POSIX has a chapter titled "Utility Conventions" giving general guidelines for how tools should behave. Its description of how to format "usage" messages and command-line arguments is quite useful! However, we soon run into things which didn't manage to get standardized or written down.

One convention of many "Unix-style" utilities is that they often produce minimal or even no output in normal situations, and that they normally run in a "one-shot" or "batch" fashion rather than being user-interactive like the "standard C" example. There are reasons for this (such as the ease of constructing shell scripts and pipelines), but this is an idea which I originally had to learn "orally" many years ago, rather than via more-formalized written means.

As we try to refactor the code to work this way, one question comes up — what should we do when there's an error (such as an invalid number of sides)? A number of utilities that I use seem to have a common convention for reporting errors (i.e. printing the name of the program before printing the actual error message), but what actually is this convention? It turns out that this originally came from the GNU coding standards! I did not know this until this experiment, and the fact that I didn't doesn't reflect well on the success of the mission of the GNU project.

After I finished modifying the code to work in a "Unix-like" "one-shot" fashion, I ran into an issue during testing (that the standard C implementation also shares but manages to hide better) — the numbers it generated stopped being random, but only on macOS. It turns out that it isn't actually specified how rand is implemented under the hood, and the macOS implementation doesn't mix the bits of the seed around very well until you generate at least one random number.

POSIX specifies a different pseudo-random number generator in the form of the rand48 family of functions. This has well-defined behavior, but it is still not a "good" random number generator. This might not matter for playing TTRPGs, but it can become a problem when the stakes get higher.

Unfortunately, "good" random number generators such as getrandom(2) or /dev/urandom aren't actually specified in POSIX (even though they are reasonably-widely available).

This is a huge problem of slow-to-respond standardization processes! They run the risk of becoming increasingly irrelevant, and the issues which they had hoped to solve (e.g. portability) once again become everybody's problem. This applies not just to POSIX but to everything, including C's slow efforts to modernize itself.

From this experiment, I've managed to gain a newfound appreciation for people such as Julia Evans who have been continuing to disseminate "basic knowledge" about how operating systems and developer environments work.

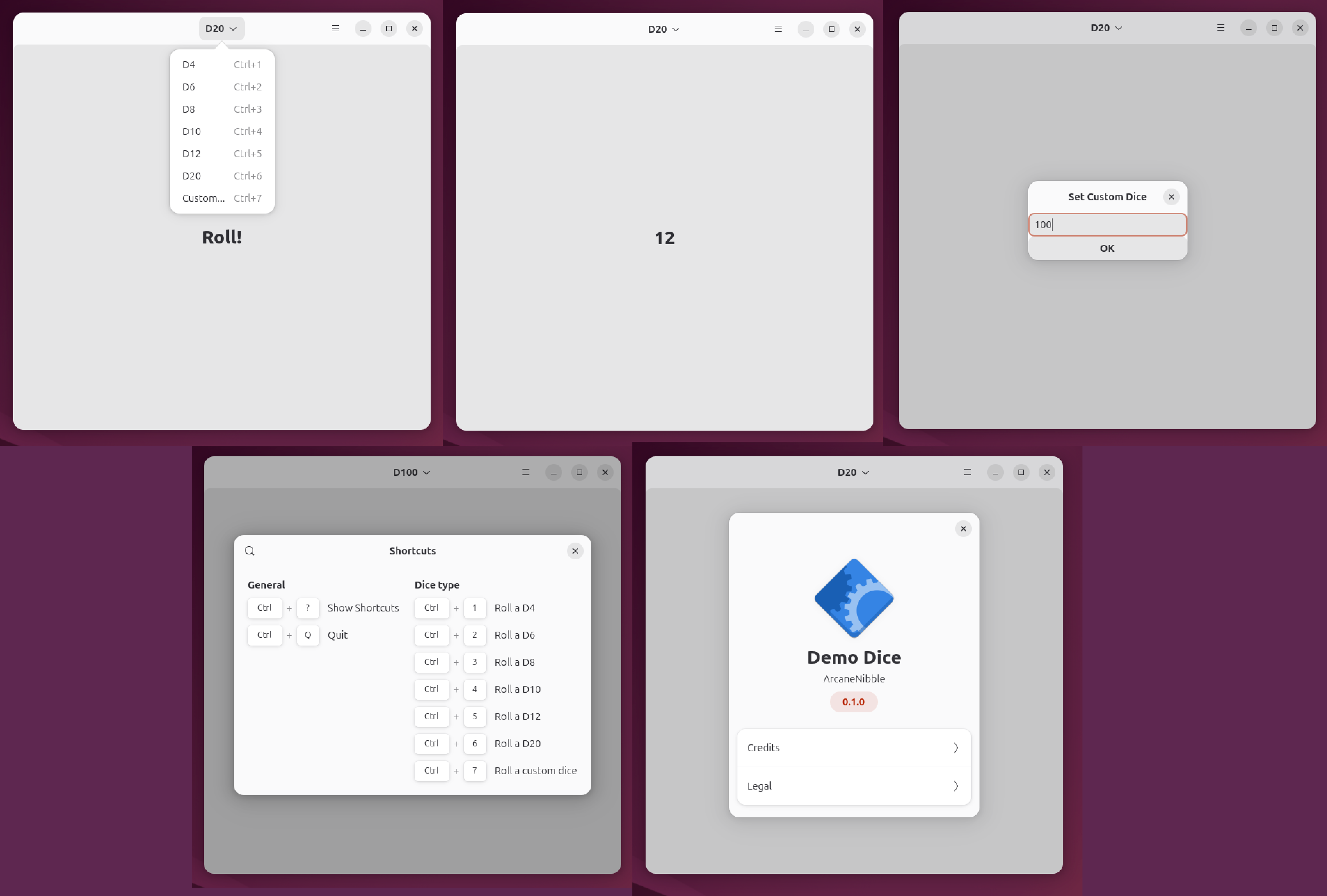

GNOME/GTK

The next platform I chose to test out was GNOME, as this is the default desktop environment for popular Linux distributions such as Ubuntu and Fedora. At least in my mind, GNOME or KDE on Linux are the platforms most associated with the "free and/or open-source software" movement (sorry, fans of Hurd, the various BSD flavors, or "minority" desktops such as LXDE, Cinnamon, and MATE).

GNOME has a rather nice-looking developer introduction page listing multiple choices for programming languages to use with it. Because I wanted to try out the "low-level, native" experience, I read through the documentation on getting started using C. From browsing around the documentation, I quickly also found GNOME's Human Interface Guidelines. The recommended workflow was to use GtkBuilder XML to build UI and Gnome Builder as an IDE, compiling applications using a Flatpak SDK. Overall, GNOME felt like it should be a nice environment to develop for!

Unfortunately, once I actually got started, the experience of developing GNOME software ended up being extremely frustrating. The documentation (as well as the entire project) felt "incomplete" — not because any specific code objects lacked documentation, but because the documentation which did exist didn't really succeed at building up mental models and conceptual understanding.

For example, the introductory documentation makes almost no mention of GLib or the GObject system which underlies all of GNOME and GTK. Understanding this is extremely important because there is a lot of complexity involved in a cross-language object system usable from C code as well as higher-level languages, and this system is involved when responding to user actions. In fact, GObject feels so conceptually underdocumented that, until this experiment, I actually had no idea what GObject even was or did (despite using GNOME software), and I had no clue that the GNOME project had powerful functionality like this!

To continue on the point about "conceptual understanding", I still don't understand e.g. why some parts of the application use "actions" to handle events while dialogs have to use "signals" instead ("actions" and "signals" also have totally different mechanisms for specifying handler functions, so they're very not interchangeable!).

The debugging experience with the GNOME ecosystem repeatedly resulted in situations of "nothing happened (but something should've), and now I have no idea why". For example, mismatching the types in g_simple_action_new vs in the GtkBuilder XML resulted in menu items that were greyed-out and disabled, and I had no idea whether I had written the XML incorrectly, forgot to set an "enable" flag somewhere, or made a different error entirely. Likewise, attempting to set up translations repeatedly resulted in "it just doesn't load the translation", and I had no idea what step in the build process I had missed. (As far as I can tell, translations simply don't work in the "latest" version (which is the default) of the Flatpak SDK. Selecting a different version, such as "48", magically works.)

Persistent settings were stored using GSettings, which is a mechanism for storing typed information according to a schema. In theory, this allows for arbitrary other parts of the desktop environment to interact with and understand a given application's settings. In practice, this didn't work (the settings couldn't actually be found by e.g. command-line tools) for some reason relating to Flatpak, and in fact integrating with GSettings made it no longer possible to launch the program locally for development (it would crash on launch because the schema wasn't properly "installed", although this somehow magically works without "installing" the schema when building a Flatpak). Yet again, this would be much easier to understand if the documentation were better at explaining context, "why?", and overall architecture and vision.

Overall, I really wish GNOME was good! Unfortunately, in its current state, it kinda isn't. What I have heard repeatedly from other people after doing this experiment is that GNOME keeps failing to listen to, communicate with, and value contributions from power users and other "outsiders". In my opinion, it really shows, as many of the struggles I ran into are likely already well-understood and internalized by regular GNOME developers.

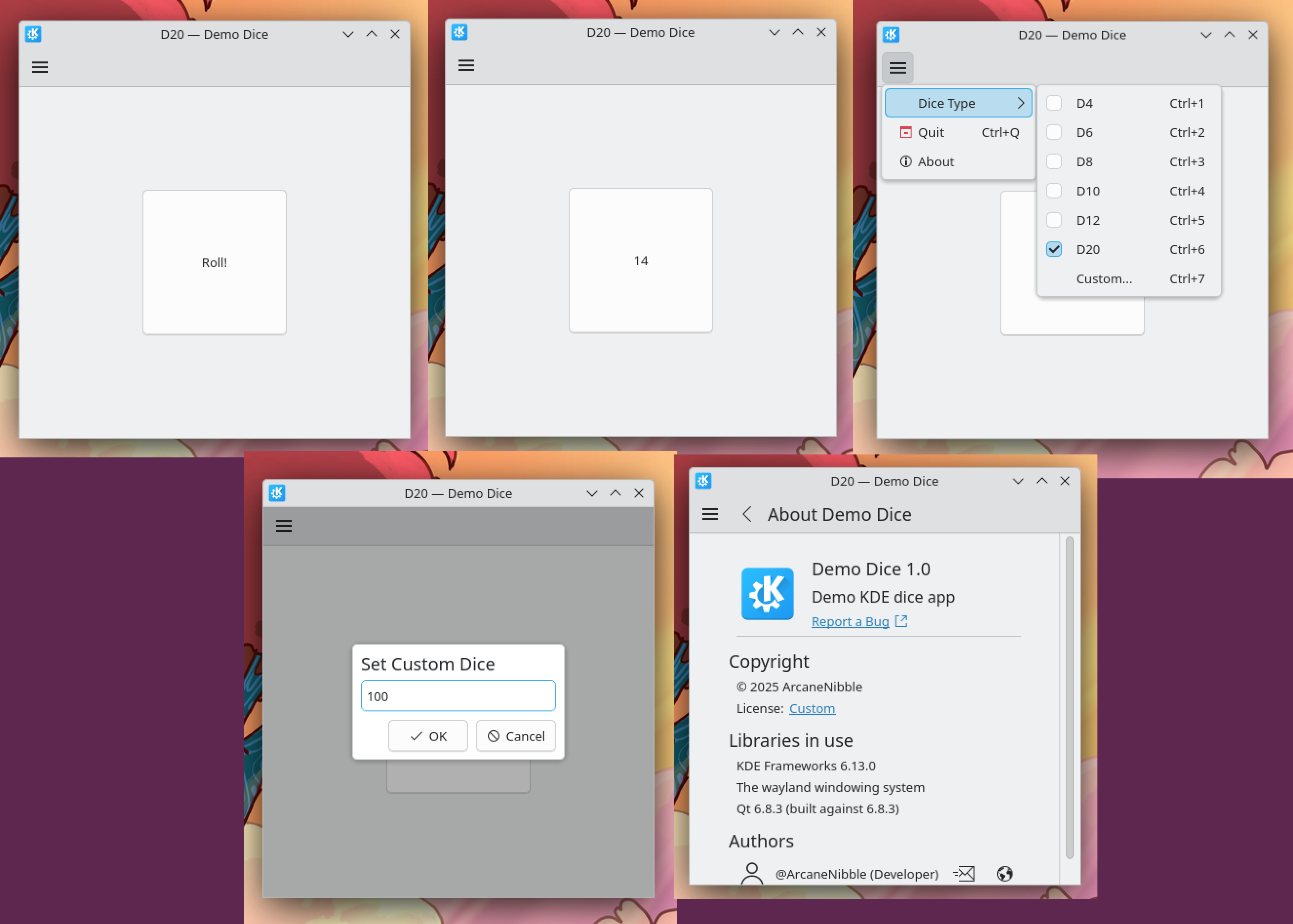

KDE/Qt

As mentioned, the other "major" Linux desktop environment is KDE, and so I sought to try it out next. KDE's developer documentation pointed me at using the Kirigami framework using either C++ or Python, of which I chose C++.

KDE's documentation felt somewhat haphazard and disorganized in comparison to GNOME's, but it is "task"-focused and fits well with the way I prefer to work (i.e. I'm not complaining, but other developers might).

KDE's tutorials unfortunately run headfirst into wider C++ platform problems that GNOME managed to avoid by recommending Flatpak. The tutorial suggests to use CMake to locate its library paths and compile your application, but CMake has a bit of a reputation for unhelpful and confusing error messages. The vast majority of the frustration I encountered while developing a KDE/Qt application was caused by CMake rather than by the UI frameworks themselves, with issues such as:

- giving an unhelpful message that it couldn't find "ECM", rather than correctly immediately detecting that Ubuntu 24.04 LTS simply doesn't have KDE 6 (but does have Qt 6)

- needing to write

KF6::ConfigCorein one location butConfig(noCore) in another - giving a completely inscrutable

No TARGET 'something' has been created in this directory.error when attempting to build translations using copypasted steps from the KDE wiki- I still don't understand what this error actually means, but changing

TARGETtoOUTPUTmagically fixed it

- I still don't understand what this error actually means, but changing

- crashing instantly in qemu-user when attempting to cross-compile a Flatpak

Once I had sorted out (or ignored) all of these errors, developing software using Qt and QML was quite comfortable and straightforward. The details which I had struggled with in GLib/GObject are nicely explained in Qt's signals and slots documentation. Although I chose to entirely embrace KDE frameworks, KDE felt like it was less-opinionated and much more open to piecemeal adoption (e.g. many KDE apps do not use Kirigami, and I had to specifically choose to even use KConfig).

For better or for worse, I believe KDE benefits significantly from Qt being widely used by "ISVs" outside of the Linux desktop ecosystem (e.g. on industrial HMIs and automotive infotainment systems). This commercial interest and Business™ probably yields a lot of opportunities, demand, and money for Qt to document the details needed for creating bindings between UI and code.

KDE and Qt tended to be louder with errors, usually at least printing something to the terminal when something went wrong. In one case, errors were even reported by dumping an "ugly" error message directly into UI text. This behavior greatly reduced "nothing happened" debugging frustration.

Persistent settings were stored using KConfig. Unlike GNOME, this doesn't require setting up a schema. Other than the CMake confusion, it was very simple to store and retrieve one single value. In fact, KDE's documentation is how I finally managed to learn about the existence of the XDG Base Directory Specification, which I hadn't ever heard of before!

Overall I quite like KDE's "get stuff done" vibe, but I do wish that the "Linux native code" situation was better.

Aside: gettext

Much of translation and localization of F/OSS software seems to rely on gettext. Without commenting on the API of it (not being much of a localization expert), I will say that cultural knowledge around this topic is woefully inadequate.

The GNOME documentation is completely useless for anyone who has not actually used *nix localization tools before and has not heard of gettext (i.e. me, before having done this experiment), and it took me a very long time to figure out that relevant setup work needed was documented by Meson, the build system, rather than by GNOME.

The KDE documentation on the other hand is for some reason buried under the tutorial for building Plasma widgets (rather than somewhere more general) or else on the aforementioned other wiki.

As someone who is multilingual (although I do all of my tech work in English), I am going to be so much louder about i18n/l10n after this experiment.

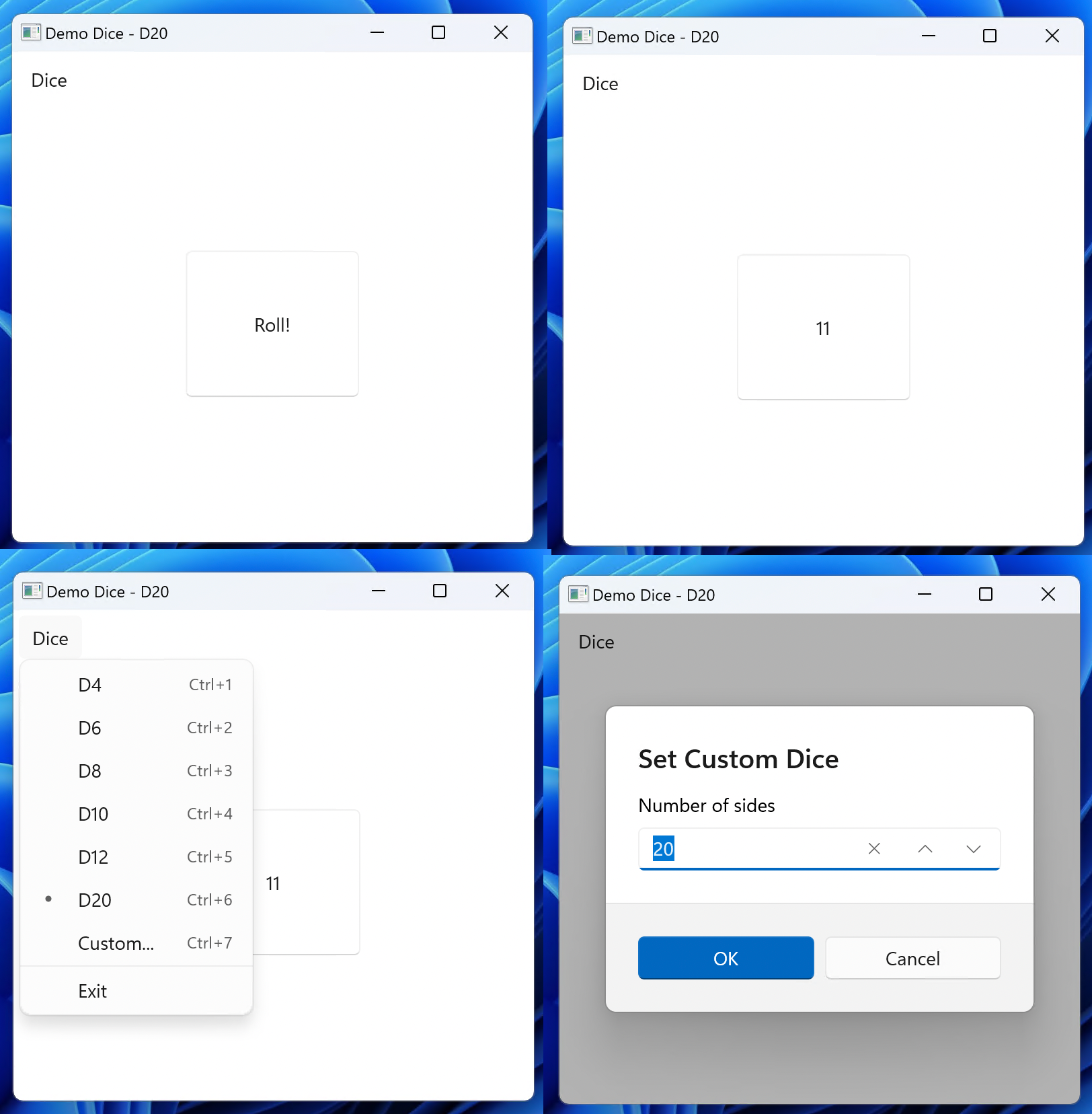

WinUI 3

In the interest of time, after trying out both GNOME and KDE, I moved on from F/OSS desktops to try out Microsoft's WinUI 3 and C++/WinRT. As mentioned, my past experience with GUIs was with WinForms, and so I wanted to see what had changed or improved in the intervening years.

Immediately, I noticed and appreciated the advantages of XAML responsive layout over the fixed pixel or DLU (dialog unit) layout of older Win32. This idea of auto-sizing has been almost universally adopted by every UI toolkit as screen sizes have become more varied. (Every other GUI toolkit in this experiment has automatic layout. This is notable only because I had prior experience with older fixed-layout toolkits on Windows.)

Unlike the previous frameworks I tried, the WinUI and C++/WinRT build process also catches and prevents a lot of errors which might otherwise occur with "stringly-typed" UI builders. Visual Studio's debugging functionality (e.g. the XAML live viewer) also works reasonably well.

Overall, it's quite an improvement for Microsoft!

However, an improvement for Microsoft means that it's still Microsoft, and the entire "rest of the owl" is a huge mess of brand confusion, clunkiness, and "why should I even bother to learn this?"

I constantly struggled to identify the difference between WPF, UWP / WinUI 2, and WinUI 3 (especially the latter two). There isn't always a clear separation between the documentation for these frameworks, and I managed to at one point get an inscrutable Windows threading-related exception when I accidentally used Windows.UI.Xaml.Data rather than Microsoft.UI.Xaml.Data.

Although I was running it on underpowered hardware, the build pipeline for this framework was slow, subjectively the slowest of all platforms tested. It certainly involved the largest number of steps, including processing IDL and XAML files followed by compiling some "modern" template-heavy C++.

C++ does not feel like the preferred "language projection" for WinRT, and many of Microsoft's developer resources seem to be encouraging the use of C# instead.

Persistent settings were stored using Windows::Storage::ApplicationData which contained several confusingly-different locations for storing key-value pairs. Once I chose the appropriate one (LocalSettings), it was straightforward to put a value into it.

Overall, WinUI 3 feels like an "it works, I guess?" technology both befitting and characteristic of Microsoft. It's not the newest, fanciest technology, but it's not really supposed to be. It might indeed help make Business™ Software™ work better. However, especially when considering all of the user-hostile features being constantly added to Windows 11, it's simply not clear why a new developer would or should bother to invest in Microsoft's ecosystem.

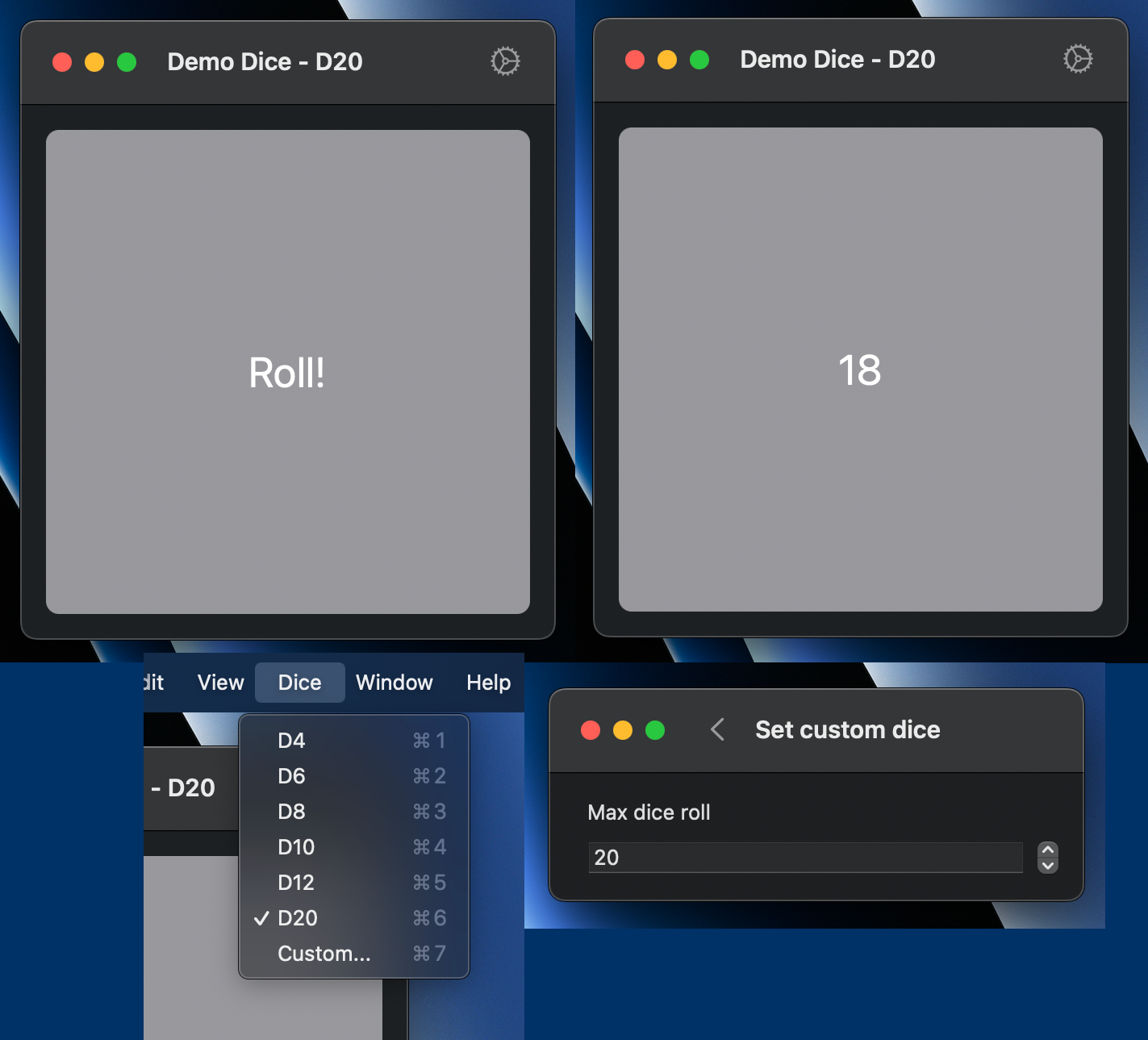

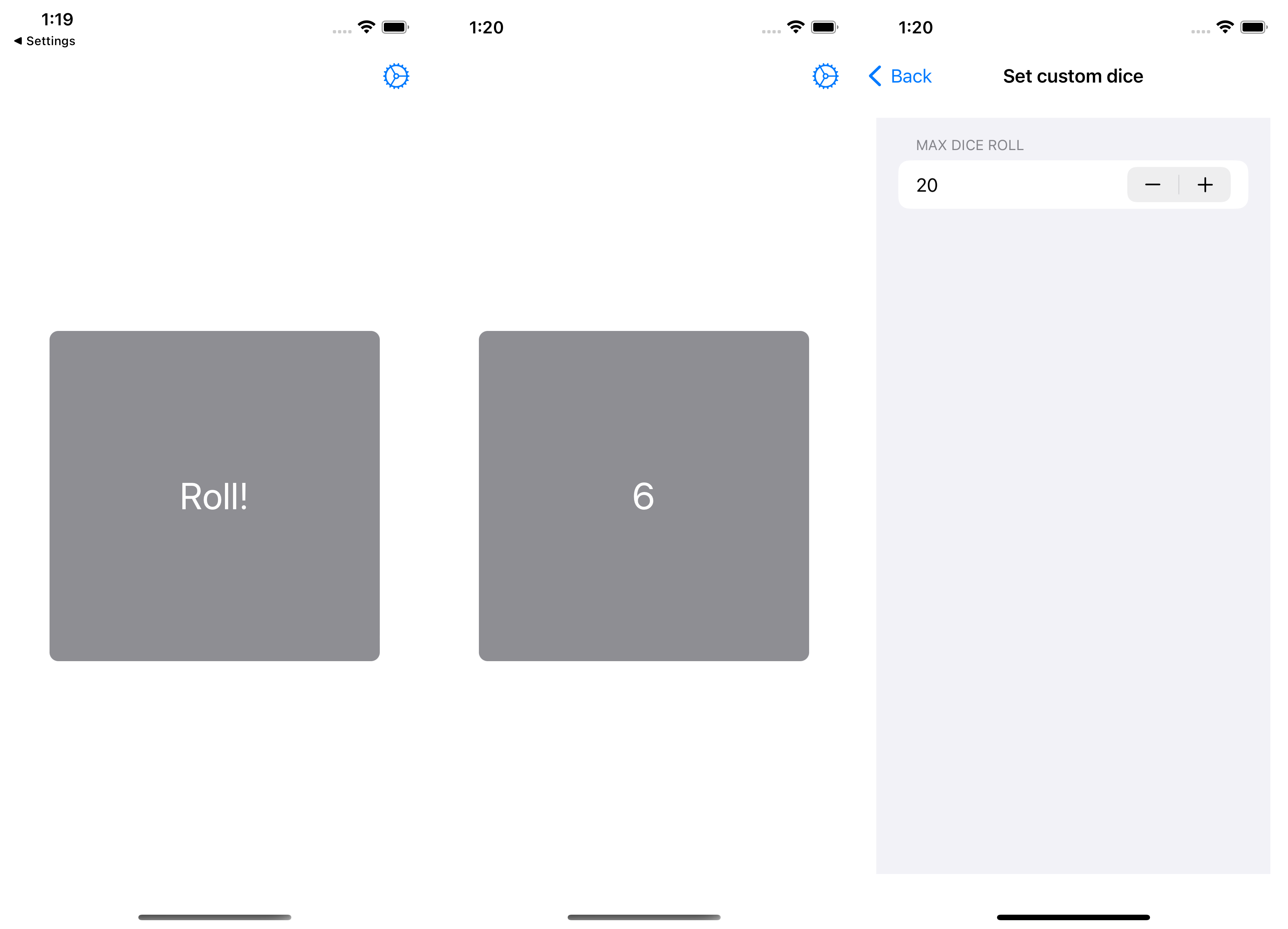

SwiftUI

SwiftUI was the first "everything as code" declarative UI framework I've ever used, and Apple has really nice developer documentation that is again an excellent fit for my particular "tasks and examples"-driven way of thinking.

SwiftUI is clearly a product of the Apple style of building very vertically-integrated, opinionated walled gardens. For example, SwiftUI and Xcode have a quite powerful live-preview capability, and the implementation of it is magic.

This level of tight integration results in something which is fun to just play around with. Unfortunately, doing so requires using Apple hardware, Apple software, Apple programming languages, and Apple's ideas about what "apps" should be able to do. This seems to result in a lot of "apps" which are quite simplified, "same-y", and otherwise a fraction of the potential of what computers can do.

Apple has also acquired a reputation for churn, and I encountered my share of that as well. I've been quite behind in updating some of my software, and so I did not have access to the SwiftUI NavigationStack and had to emulate it. The Apple developer ecosystem doesn't seem to value forward or backward compatibility — a stark contrast to the standard C example or even Apple of earlier eras.

Persistent settings were extremely easy to set up using a @AppStorage property. In the same manner as everything else Apple, it works magically as long as you don't question how or where data is stored.

Overall, I really enjoyed my limited time with the developer experience here, and I can understand why at least some people really like the Apple ecosystem as both a user and/or as a developer. Unfortunately, as someone who also very values some of the ideals of the F/OSS movement, I just cannot go all in on Apple, and I can see how restrictive this ecosystem can be and how difficult it would be to reuse anything on other platforms.

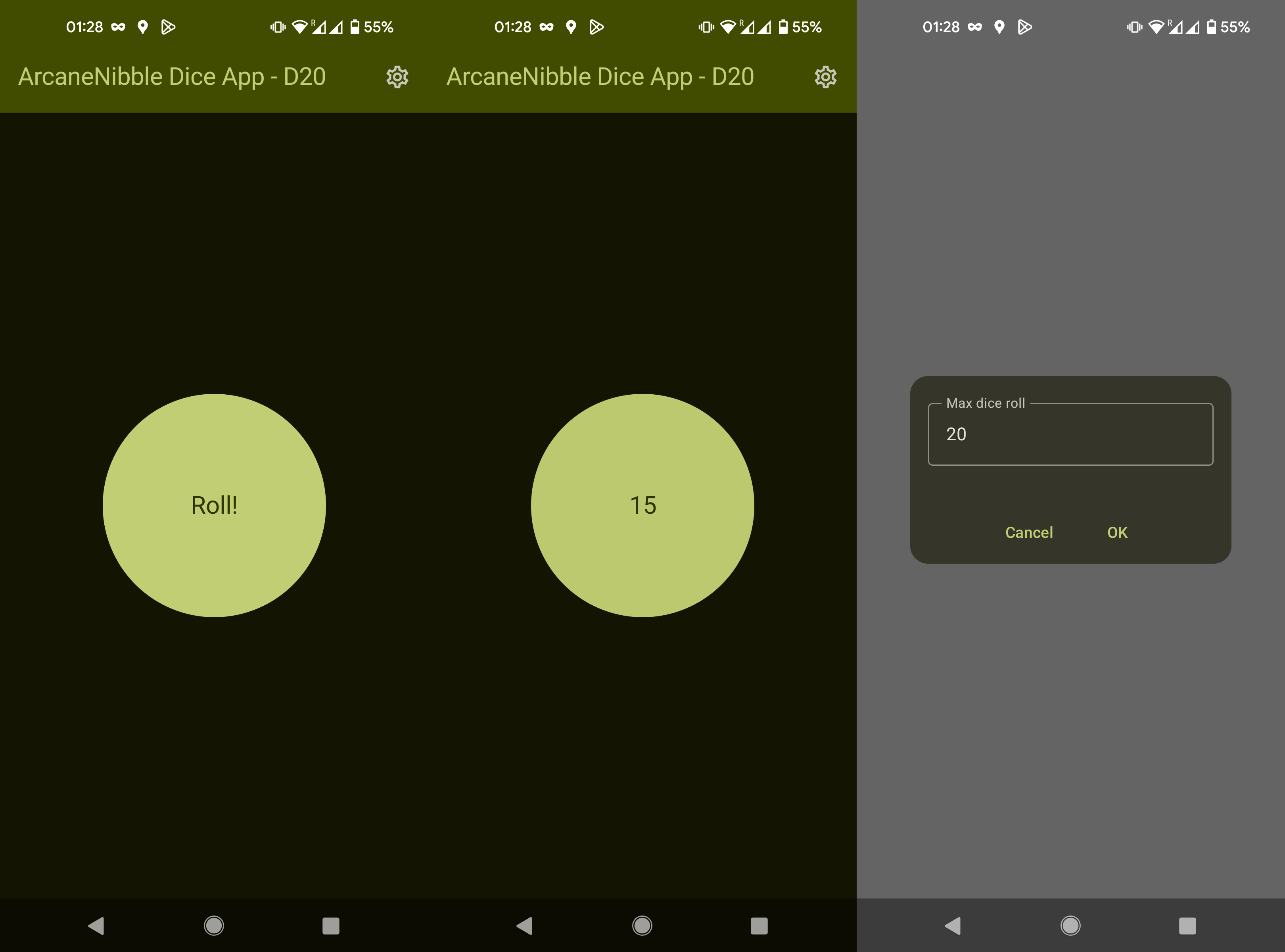

Jetpack Compose

At this point in the experiment, exhaustion was starting to set in, but I still had to try out the most popular operating system in the world — Android, where the promoted UI framework was Jetpack Compose.

To be very blunt, Jetpack Compose felt like a very soulless "I wish it were SwiftUI". The documentation and tutorials are a horrific mess, oversimplified into oblivion and not at all universally accessible nor useful.

Android's documentation is fragmented across API references, cheesy marketing-esque videos, oversimplified "codelabs", an Apple-style "tutorial", and "quick guides". All of these felt almost intentional in how they avoid explaining "how to build a complete app from start to finish". This is before we even touch lower-level APIs, the pre-Jetpack Compose APIs, etc. Despite being the search giant, Google Search often failed to find useful resources when I encountered errors.

In terms of annoyances, for some reason Android Studio seemed quite flaky around dealing with devices and emulators, and attempting to debug exceptions which occur before the app completes launching just doesn't seem to work.

Persistent settings were the most difficult on Android because, unlike every other platform, androidx.datastore.core.DataStore is asynchronous. I was never quite able to figure out how this was supposed to integrate properly into the Jetpack Compose model, and I eventually gave up and used runBlocking to turn it into a synchronous interface.

The Jetpack Compose framework itself seems to work... fine. However, everything about it feels amazingly unpolished for something released by one of the largest tech companies in the world.

It almost feels disrespectful of developer time, a product of a company that knows it is in an untouchable monopolistic position.

Wow, that was bitter

Yeah. Sorry.

Even though the experience kinda sucked, I learned a lot. I'm going to spend so much time hacking on all the things I'd been ignoring.

If you actually want to build a native cross-platform app, I'd personally recommend Qt (although I would not use CMake).