A history of "Web" tech, from a "non-Web" developer

I recently had to demonstrate to a partner how application development on Windows worked "back in the day" (using Visual Studio (not VSCode) and MFC). During the subsequent discussion, I realized that I have an unusual perspective on the history of the software ecosystem over the past decade, and that this information is useful to have in written form. Thus began this post.

The process of organizing and transferring all of these thoughts from headspace to the world of words really helped put things into perspective. I learned a lot merely by writing this, and I feel like I have much more clarity on the direction I want to see "software" and "tech" go. Despite the problems, I don't think we're at "peak tech" yet!

The prehistoric era

Many people currently seem to be waxing nostalgic about the "prehistoric" era of Web development. Unfortunately, I was a child for most of this era and thus struggle to retrieve memories in the form of a coherent linear timeline. We must make do with fragments.

In "absolute" time, these events ranged from approximately 2001 to 2010.

I first started showing interest in learning how websites worked when I discovered a combination of two desktop web browser features: "view source", and the ability to save an offline copy of a page together with all of its referenced files. The moment I managed to have a copy of a page, it was almost instinctive to want to start modifying it. I had already been introduced to the raw concept of "programming," so the idea of being able to change somebody else's website wasn't foreign or unthinkable, but the actual discovery of these browser features still relied on undirected wandering and a childlike sense of patience and joy.

Once this interest was spotted, my father tried to encourage it — he bought me a book (a physical book, made out of dead trees) on HTML and Web development. From this, I learned about the existence of CSS and JavaScript and generally got a high-level overview of how webpages were put together. These fundamental primitives are how web pages continue to work today!

I have the following concrete memories from this era:

- I somehow discovered "that" "analog clock which follows the mouse cursor" script and copied it onto one of my pages. Here is a modern implementation.

- The book made mention of "server-side" logic which I couldn't use, because I didn't have "a server"

- However, the book mentioned the use of a

mailto:URL informs as a potential poor-man's substitute!

- However, the book mentioned the use of a

- I saw a demo of Embedded OpenType in the book and wanted to use the "cool" typeface the book author was using. I bothered my father to download the EOT converter tool, WEFT, using the broadband connection at his workplace, but I didn't understand that this tool didn't actually contain the cool typeface in question.

- I discovered that double-clicking a

.jsfile opened it in this mysterious tool called "Windows Script Host". The normal Web JavaScript examples didn't work in this environment, but I didn't understand why.- Researching it using the tools available at the time led to the discovery that Windows Script Host could also run VBScript, and that you could also use this language in HTML (as long as the user was using IE).

At this time, I also had a book on "Visual C++" which made mention of Microsoft-specific technologies for this "emerging Internet era" — DCOM, ISAPI, etc. These were all far too complex for me to understand at the time, so I never looked into these any further. However, the exposure to these technologies stuck around as a reminder of what might someday be possible. (Incidentally, I seem to recall Paypal having .dll in its URLs during this era, possibly indicating use of ISAPI?)

One of the many benefits of the Web as a technology was supposed to be the ease of sharing content with others. I didn't have any friends at the time who shared the interest in taking technological systems apart, and so I did not significantly engage with the Internet as a community. (However, I do recall the first moment I discovered Wikipedia — "Wait, editing this really does change somebody else's webpage? Not just my copy of it? This is amazing! I better not break it though...")

Possibly my only interaction with sharing content happened thanks to friends who did play a certain online digital pets game. In order to show off some "because I can, because I understand the technology better" skills, I recall attempting to write CSS rules with sufficient specificity to override the background color to black across the entire player-customizable shop page.

In retrospect, this was an amazing exposure to ideas which are possible, and this happened thanks to the exposure to advanced, "enterprise-grade" technology! Although many of these technologies were proprietary and are now long-deprecated, they enabled me as child to dream big. Someday, perhaps I could also build a corporation like that...

The project, and the beginnings of the hell era

In 2013, I and a few co-conspirators started a project that attempted to (at a very high level) make robotics, embedded systems, and physical computing more accessible. This project spiralled out of control and otherwise ran into many many problems, but here I would like to focus on the "Web"-specific ones.

One co-conspirator observed that "traditional" desktop UI toolkits (e.g. MFC, WinForms, or even cross-platform ones like Qt) were quickly losing developer mindshare, and they predicted correctly that the focus was shifting towards using "Web" technologies. Web technologies seemed to offer many advantages, including being already cross-platform, having faster iteration cycles, and much more seriously exploring paradigms such as hot reloading and live coding.

At this point in time, the US smartphone ownership rate had just crossed 50%, but traditional desktop and laptop computers were still "a thing." Although companies including Google had been adopting "mobile first," this didn't seem like a reasonable choice for "serious" work.

So, how do you actually build a "serious" "desktop-first" application using Web technologies?

If you didn't live through this era, you might instinctively say "Just use Electron!" However, you couldn't "just" use Electron:

- For starters, Electron did not exist yet and certainly not by that name. The initial commit for "Atom Shell" had only been created a few months prior to our project starting

- Others' attempts at implementing this idea were mostly being done with node-webkit. It certainly made for some nice demos, and it worked well enough for more "typical" applications, but it had quite a few problems for my incredibly-high standards of "serious, professional" quality:

- It didn't have an "obviously correct" final packaging and deployment strategy for all the major desktop platforms all at once (as opposed to needing a separate build machine for each platform). This made setting up CI/CD complicated.

- In particular, it didn't have a good strategy for cross-platform interfacing with physical hardware

- WebSerial and WebUSB didn't exist yet, and so there was no "standard" way to do this

- The serialport package did exist for Node.js, but it requires native code

- Native code in the Node.js ecosystem was usually built with node-gyp, which didn't have a clear cross-compiling procedure

- Node.js and the npm ecosystem had existed for a few years, but they weren't yet the consensus JavaScript ecosystem!

- Node.js code wasn't Web code, and you needed special tools such as browserify to turn it into such

- npm mostly didn't contain Web code, and there existed separate package ecosystems for the web such as bower

- Needing to use a bundler tool in the first place wasn't the consensus workflow

Looking at the state of the ecosystem (and not yet feeling comfortable as an "active" participant in it), I concluded that it was too janky for my tastes. Instead, I dug around and came across a piece of technology which seemed like it should've solved all of the above problems: XULRunner, the underlying engine which powers Firefox and Thunderbird. This seemed like the perfect choice — full access to Web technologies, capable of interacting with traditional WIMP desktop ideas (i.e. legacy non-Web technologies), a documented deployment procedure, and with ctypes-style FFI built-in (at no point requiring a native compiler).

It was obvious that the Mozilla-specific technologies (XUL and XBL) were dead-end, so the plan was always to use them as little as possible. For the project, we created a minimal XUL document which immediately loaded a HTML5 document. We would only use nonstandard technology for the ever-diminishing functionality which wasn't yet accessible to HTML.

The myriads of incompatible module systems

Unfortunately, we quickly ran into something which wasn't yet usable — modules!

In order to develop code with meaningful abstraction boundaries, many programming languages have tools for dividing code into modules. Unfortunately, at the time, JavaScript didn't have one. Or at least, it didn't have one.

The modern consensus for modules seems to be to use ES6 modules, or ESM. ES6, the 6th edition of the ECMAScript standard (a formal document describing how the programming language should work), was being actively developed, and browsers were slowly rolling out individual experimental features one-by-one. Unfortunately, ESM was not one of them.

I clearly understood the need for a module system from the very beginning, and the first choice I reached for was Mozilla's proprietary implementation. Although it was nonstandard and had unusual semantics, it existed and worked and was being used extensively throughout the Mozilla codebase. Because npm was not yet the consensus JavaScript package manager, I didn't see a good reason to take a dependency on it nor on Node.js (after all, we already have a JS engine inside XULRunner!). The project already had a preexisting build system duct-taped together out of Python and shell scripts, further amplifying my "why do we need another language?" hesitation.

As the JS ecosystem continued to grow at an accelerating pace, npm started gradually winning the package ecosystem war. At the time, I was not familiar enough with social dynamics to see this, but I did see the consequence wherein its module format, CommonJS, increasingly took hold.

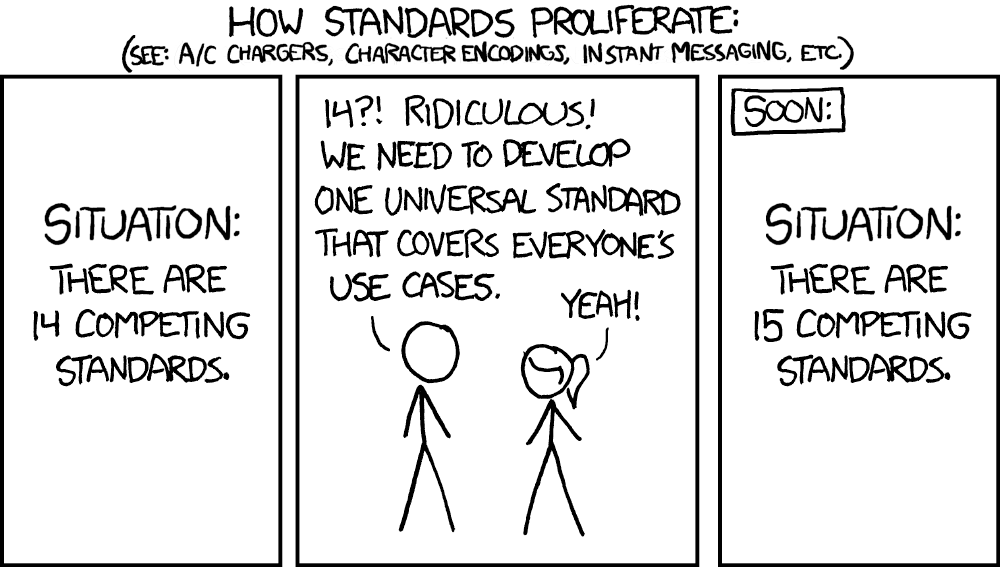

Another module system which existed at the time was AMD, or Asynchronous Module Definition, and attempts were also made to unify the formats into UMD, or Universal Module Definition. This post gives examples of each of these formats. In short, the ecosystem looked like this:

As CommonJS gained ground, the project migrated all of its own modules to the format. However, as bundlers were not yet a universal part of the workflow, I once again ended up going against the grain by choosing to use Mozilla's Jetpack SDK (which was already part of XULRunner and thus didn't require installing or deploying anything extra) as the CommonJS implementation.

The framework wars

As someone who grew up programming with "traditional" UI toolkits, I had no instinct to want a "framework" for building the application. I embraced utility libraries like jQuery, but I had to be actively shown what was popular on "the Web."

At this time, AngularJS (Angular 1) was the popular "large" framework for helping to build "single-page applications." Its bidirectional data bindings promised to simplify a lot of manual work I was doing, and so I decided to go for it. The model for integrating AngularJS into the page was straightforward for someone familiar with the "old" way of doing things — you just had to load it in a <script> tag. Everything else was "just JavaScript."

However, as the project got further along, the AngularJS programming model was proving to be rather clunky. Along with having a lot of "magic" (i.e. hidden details and assumptions) in its implementation, it didn't seem to be saving us as much work as was promised. Someone on the team was itching to make a change, and the brand-new framework at the time was React.

At the time, the React tutorial didn't feel particularly compelling, and JSX felt like an unnecessary step slowing down application launch. I certainly perceived it as quite possibly yet another fad.

Miscellaneous woes

In start contrast to all of the above-described ideas, one feature which I eagerly adopted and which in many ways drove design decisions was asm.js (which was also new at the time).

Because we were dealing with embedded systems, we had to deal with C code. C has a reputation for not being very beginner-friendly, so (after a massive detour) we decided to use Lua for high-level logic and use C only for drivers and real-time control (MicroPython once again didn't exist yet).

One design requirement was that we wanted to be able to run this high-level code on a computer in simulation in addition to on a physical system. This meant that we needed a way to run Lua inside our desktop application. To stay aggressively cross-platform, I chose to handle this by compiling the Lua interpreter to JavaScript (WebAssembly was years away from existing, and asm.js was the early attempt to show why it would be useful and wanted).

Even though this was also experimental technology at the time, Mozilla had already shipped ahead-of-time-compilation optimizations for asm.js, and one of its main selling points was "it's just JavaScript." In theory, nothing special had to be done to make it work (on the "library consumer" end), and it'd fit right in, or so I thought. Oh how wrong I was!

Even though asm.js "just produces JavaScript code," it doesn't culturally fit the Web ecosystem. C code simply has vastly different assumed knowledge in the developer. First of all, the toolchain for building asm.js, Emscripten, didn't have Linux binary releases yet. This didn't bother me, as I was familiar with having to painfully glue together arm-none-eabi toolchains for the microcontroller, and so I just compiled a tarball that was shared between my development machines and my CI server. However, wrangling compilers wasn't a typical Web developer activity.

Even worse, because I was using Linux as my primary development platform and as the CI platform, the entire rest of the (monolithic) build system was full of Linux-isms and could't run on any other platform. At the time, I didn't understand why this was a problem as the final build artifacts themselves were indeed truly cross-platform, but this further alienated Web-focused developers.

At some point, this issue became so heated that a co-conspirator hacked together a way to bypass the duct-taped-together build system (by relying on periodic snapshots of all the annoying-to-generate outputs). This hack included a script which launched the operating system's copy Firefox as if it were XULRunner, loading our application in debug mode instantly (because the application didn't use npm or a bundler workflow, this just worked).

Unfortunately, this wasn't enough to resolve all of the culture clash. Even though we now had a Lua interpreter in JavaScript, the API surface was still a C interface. This meant that passing strings from JS to Lua involved understanding very un-JavaScript-like concepts of heap allocations, pointers, ABIs, asm.js's particular implementation of these, and the Lua VM's virtual stack. Because both ends were dynamic languages, I naturally wanted to abstract this away, and I chose to do so by writing automagic thunk-generating functions between the languages. I then immediately suffered the consequence that nobody else was able to understand how this worked.

By this point, the project had ballooned in scope and used Python, Lua, and JavaScript in different places. Much haphazard porting of libraries between the languages happened when we ran into unavailable functionality.

I should've learned many painful lessons about programming languages, what they assume about developers, and how they get used by humans in practice, but neurodivergence meant that this lesson would take the next decade to truly sink in.

The end, and the true rise of Web

At some point, I crashed and burned and the project failed.

I didn't pay attention to many of the associated technologies for several years.

The dust settled on the mess. Many problems were fixed. Some problems got worse.

"Web" proceeded to eat the entire world. More and more applications are now developed using Electron. Mozilla managed to lose just about every advantage that they already held.

npm won out as the definitive package manager and package registry for JavaScript, despite some spectacular flaws. More generally, having a "definitive" package registry grew into an expectation for many programming languages:

- Some languages already had one: Perl had CPAN, Python had PyPI, etc.

- Some languages' package registries grew massively, such as the JVM's Maven Central

- Some languages gained one, such as .NET's NuGet Gallery

- New languages such as Rust released to stable with crates.io

Using a bundler became the expected workflow for frontend development. This made it much easier to integrate code together, and this extended to beyond just JavaScript (for example, bundlers like Webpack also handle images, CSS, and WebAssembly).

Composability in Web frontend development became much more possible and much smoother now that these issues were settled.

React ended up not being a fad, but other web frameworks continued to proliferate. Massive ecosystems grew up around them. This continually-shifting environment seems to have discouraged the creation of detailed, old-school tutorials such as books — they'd quickly fall out of date and become irrelevant. "Getting started" became increasingly dominated by and dependent on quickstart tools and project templates.

In contrast to the tooling of old, the new ways of working now seem to discourage users from knowing how the internals work. In the "prehistoric" era, users needed to understand. Tools were simply not yet capable of hiding much of the complexity. Solving these issues made some types of programming ("I want to quickly launch a service which does X") more accessible at the risk of gradually forgetting the fundamentals and the power of incremental discovery ("I was inspired after clicking 'view source' and built up from there").

If we forget too much, we run the risk of getting stuck where we are, with no chance of further improvements.

Let's not do that.